The snow last week didn't last long. It drifted up, inches and inches,

fluffy and cozy, but it was a warm snow, with big fat flakes, and started

melting soon after. It’s been melting steadily now for days, and this morning I

found big patches of bare ground, especially in the open places. I can’t walk

out in it much, everything’s mud, but it’s a sight. I haven’t seen bare ground

since I’ve been here.

It’s weird, every other time I’ve come to a new place and stayed it’s been

in the summer or the fall—not counting ski trips, I’ve never been anywhere for

the first time in the snow. So now I’m finding out all sorts of things about this

campus that I never knew, because they were under the snow.

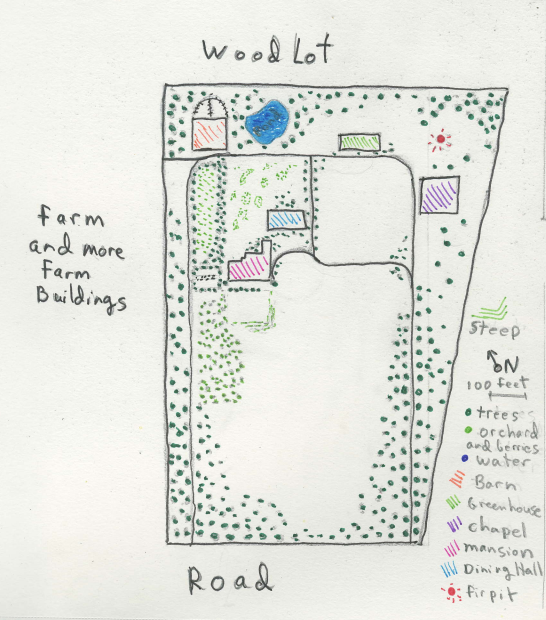

For example, the open area out near the back of the barn isn't a clearing,

it's a pond. It’s not open water yet, but I noticed that grass was appearing from

under the snow everywhere else and not there, so I got curious, braved the mud,

and walked out. And it’s a pond.

Elsewhere, I noticed there’s something odd about the grass. It’s longish and

uneven, and there are little shrubs in it in places, prickly things, with

broken, chewed-off stems. Chewed? Frozen chucks of horse turd are coming out of

the melting snow, too. These aren’t lawns, I don’t think, they’re pastures. Of

course that makes sense, there are sheep and goats and horses here, and grazing

them on campus would reduce the amount of hay we need to buy. And I don’t think

I’ve seen a lawnmower anywhere.

And the roads aren't paved. The campus roads weren't plowed, they just

packed the snow down and added gravel and sawdust for traction, but I'd always

thought there was pavement under there. Instead, it's just gravel and little

chunks of crushed cinder block. Of course, the roads are melting slowly,

because the snow is packed, but there are a few open patches.

In the open patches of road I’m seeing, here and there, pieces of broken asphalt,

just crumbs, little chunks, so obviously the roads were paved at some point. I

asked about this, and apparently when this school moved in the campus was s dilapidated,

but fairly standard, boys’ private boarding school. There was a school

building, several free-standing dorms, a gym, an athletic field…the place had

been abandoned for five years, and some of the dorms had been closed even

before that, as enrollment dropped, so everything was grown over and moldy and

starting to fall to ruin. The top floor of the Mansion had even burned in a lighting-struck

fire. So, when our school came in they had a lot of fixing up to do, and they simply

razed the buildings they didn’t need. They unpaved the roads, rehabilitated the

ground in the athletic fields and turned it into our farm, and apparently spread

the cinderblock and concrete pads in chucks to gravel the roads.

It’s interesting that there were obviously cinderblock buildings here,

apparently a lot of them, but there are none here now. Presumably the

better-built buildings survived abandonment better, and given the choice

between saving the Mansion and saving a cinder-block dorm, I’d save the

Mansion. It’s a beautiful building. But, and I’ve thought of this, a parent

coming up the hill of the main driveway would not have seen cinderblock

buildings first. They would have seen the Mansion and, coming a little closer,

would have seen Chapel Hall, which is weirdly imposing and, as I noticed my

first day, looks vaguely collegiate, being brick with ornate white trim.

But they would not have noticed any

cinderblock buildings. If all the buildings were where I think they were, the

more cheaply constructed places would have been either out of the immediate

line of sight, hidden by trees, or behind Chapel Hall. I never thought about it

before, but a private school has to appeal to parents, or their source of

revenue dries up. I don’t suppose the business plan required being honest about

how students actually live.

The message of the campus now is very different, if there even is an

intended message. Strangers come here so very rarely. I used to work at a

landscaper’s when I was in high school, so I notice landscaping, and the campus

is definitely planned, but it’s hardly manicured. Again, there are layers of

history—avenues of old trees lining the long driveways and an orchard of

apples, pears, and peaches must go back to the farm. Foundation plantings of

shrubs and specimen trees must date to the boarding school, because they are

associated with buildings that are. But the straight lines and clean plantings

are all either added to or interrupted. Nothing here is straight, nothing looks

cleaned up. Most of the plants look kind of odd, maybe they’re species I’m not

used to, or something, I can’t tell. It looked kind of normal and sedate under

the snow, and I imagine it must be riotously exuberant in the summer, with the

grass and flowers waving in the pastures and everything green, but at the

moment winter-bare trees and shrubs reach their crooked twig-fingers out from

wild hollows across the mud and rotten, slushy snow of spring, and it looks

kind of Grimm.

There’s so much history here, not that I know most of it, but I can see the

shadows of former incarnations of this place. Like the chunks of cinderblock

and asphalt from the boys’ boarding school, or the big, flat place on the front

lawn—I mean, pasture—a big square, with a short, steep embankment on one side

where it rises to meet the more normal-looking land in front of the Mansion,

and a longer, equally steep embankment where the ground falls off to meet the

natural slope on the other side. There must have been a building there, long

ago. Perhaps it was a barn, back when this was a wealthy horse farm?

The Mansion itself shows its history in layers. Once it was obviously a

large, but not ornate stone farmhouse, but that was expanded with extra rooms

and a new wing. Then, after the fire, we added the fourth floor (I don’t think

the building got much taller, though; the first and second stories have

fourteen foot ceilings while the third and fourth floors have eight foot

ceilings and reportedly are not as cold at night as I am), better insulation,

and passive solar heating measures like big windows on the southwest side. The

first floor is grand and much of it looks a lot like it probably did back in

the heyday of the horse farm, but the floors get progressively…less traditional

from there. There are photovoltaic panels on the roof.

And when I say the ground floor of the Mansion is traditional, I mean it is

traditional in mood and in a kind of general overview, but not in detail. The

Great Hall is all honey-colored wood paneling, with a grand staircase winding

up and around an open, vertical well of dusty, sunlit space rising three

stories up to a skylight in the floor of a patio the masters have up there. It

looks like a good place to host a ball. There’s a sunroom, called the Green

Room, off to one side full of plants and white wicker chairs and a little

fountain with fish in the basin. Except that the fountain is solar-powered, it

looks rather Victorian. The Rose Room, where we have some of our seminars and

things, is basically a sitting room, with rose-colored wallpaper and lots of

dried flowers—except

the pictures on the

walls are all antique-looking drawings (and even photographs!) of fairies and imaginary

animals. The Bird Room, next to it, is a formal dining hall all in dark wood

and glass display cases, but most of the display cases hold, not china, but

huge dead insects and spiders, mounted and pinned. Fossil shells, crystals, and

fans of feathers take up space. Eggs of exotic birds collect dust on their mottled

shells. Taxidermied birds—a raven, an egret, a gannet—and the mounted skeletons

of a hawk and a chicken all regard each other from the tops of shelves and

ancient writing desks. They’re all labeled, or I wouldn’t know what they are,

and I’m sure none of them except the chicken are new. The whole thing looks,

again, Victorian, but slightly askew. There’s a bench along the window, and you

can sit there and look out into an almost Japanese-looking garden where

copper-roofed bird-feeders in the shape of pagodas attract real, live birds.

Entirely modern binoculars, two pairs, hang from wrought-iron hooks by the

windows, and they are so powerful you can sit there and find out if birds have

nose-hairs, if you want to.

Sometimes, in the Mansion, you can hear voices, or people moving, near the

stairwell, and nobody is there.

And how did I get off on this tangent of description? Andy is back from

rehab, a lot clearer-headed than he was when he went in. He seems to be mildly

obsessed with the bicycles; he can’t seem to let go of his guilt. Aidan is home

from the hospital and growing well. Kayla is actually nursing him, so she

carries him around with her most of the time—I can’t say I ever expected to see

a twelve-year-old’s breast, but if even if I had, this would not have been the

context I anticipated. But unlike an adult mother she never has to worry about

babysitting. If Kayla wants to do something else, or if something goes wrong,

Sadie figures it out. And Aidan sleeps—or refuses to sleep—on the fourth floor

with Sadie, not in the dorm with us. We’re on the second floor, and Nora told

me that from the third floor they can sometimes hear the baby cry at night, but

we can’t. Kayla gets her sleep, or stays up late partying with us like a

teenager. No one will give her any alcohol, though—obviously, she’s

breastfeeding, but there’s her age, too. She complained that her mother always

let her taste drinks when she was a kid, but Meg, who is kind of matronly, said

“well, you’re not a kid anymore,” and Kayla hasn’t asked again.

It’s ten days till spring, or mid-spring, the way Kit says it, since she

says spring actually began in February, at Brigid, under all that snow. I don’t

know what they do here for the spring equinox, but I know enough to guess that

they’re going to do something. But you know what? I’m seven years older than

Kayla, I can vote, and Meg lets me drink even if the law doesn’t, but there’s

still enough of the boy in me that I’m really hoping that on the equinox we’ll

get chocolate.

[Next Post: Friday, March 15th: Interlude]